A Vermont ski pioneer blazes trails for the future

Clem Holden grew up skiing on the forested mountainsides of Bolton Valley, and now as he nears his 90th decade the perennially threatened land is on the verge of permanent preservation

Click on photos to enlarge.

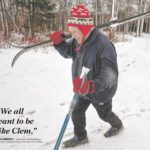

“We all want to be like Clem” – Cilla Kimberly

By DAVID GOODMAN Free Press Correspordent- December, 29th 2012

Winter 1939 – Clem Holden, a trim, fit 17-year-old man from Burlington, is skiing up a logging road from U.S. 2 to the top of Bolton Valley. His destination is Bryant Cabin, a simple wooden structure located high in the mountains. Old man Ed Bryant, who lives along U.S. 2 but owns much of the land above, gives Clem the key to the cabin for him and his friends to use. After three or four hours, Holden and his friends arrive at the cabin. They have the entire horseshoe-shaped valley to themselves to ski. They revel in the powder, the camaraderie, and the spectacular views of the frosted Green Mountain summits. At day’s end, they whoop and holler as they descend the bumpy powder-choked logging road.

Winter 2012 – Clem Holden, a trim, fit 89-year-old man from Burlington, is skiing slowly but steadily to Bryant Cabin. Old man Bryant died nearly 70 years ago, but the young man who once loved to ski around Bryant’s rustic cabin continues to visit.

Some things have changed: Holden drives his car five miles up a paved road to the base of the sprawling Bolton Valley Ski Area. He skis to Bryant Cabin in about 45 minutes on a well-graded trail.

And some things have hardly changed at all. Holden skis around with some friends, smiling broadly as he relishes the powder and the spectacular views over the valley.

Clem Holden sits in a comfortable stuffed chair in the North Avenue home in Burlington that his wife Sylvia grew up in. Photos of their two sons and grandchildren adorn the wall, as do images of high and wild mountains where he has skied. His tanned and weathered face is framed by a shock of close-cut bright white hair. He looks as if he wears a permanent crown of snow.

Just a few months from his 90th birthday, Clem Holden can still be found skiing at Bolton Valley nearly every chance he gets. This lifelong passion for exploring snowy places and creating enduring trails has earned this happy and humble man the distinction of being “one of the forefathers of backcountry skiing in Vermont,” declares Jim Fredericks, executive director of the Catamount ‘frail Association. Now, Holden’s cherished but perennially threatened Bolton backcountry is on the verge of being preserved for future generations to enjoy.

Born in Buffington in 1923 into a family of eight children, Holden has ridden the first chair through the dramatic rise of Vermont’s ski industry. He skied in the opening seasons at both Stowe (1937) and Mad River Glen (1948). He never imagined that the humble pastime of sliding on snow would one day mushroom into a billion dollar industry.

Holden got his start skiing on outings with the Boy Scouts. He explains that most of Burlington’s Boy Scout troops were affiliated with churches and they would not ski on Sundays.

“I was in Boy Scout Troop 1, which was affiliated with the Unitarians,” he says with a mischievous grin. “They just went into the mountains and didn’t care about getting to church.”

After graduating from the University of Vermont in 1941, Holden got a job working in human resources in the aircraft industry in Connecticut and New Jersey for United and Pan Am. But New Jersey “was too far from skiing,” so he took a job in Montreal with Canada Air. He eventually went to work in Ottawa for the Canadian National Park Service. He would cleverly schedule work-related trips in the winter to the mountains of western Canada where he would always add a few days to go skiing.

One day while standing in a lift line at a ski area near Ottawa, Sylvia noticed that the “people who were cross-country skiing looked so happy and healthy, and we were just standing in line. Pretty soon we weaned ourselves from downhill skiing.” The Holdens fell in love with skiing =- groomed trails in the backcountry. They traded their downhill skis for cross-country skis and never looked back.

Click on photos to enlarge.

In the 1960s, Clem Holden was asked to help clear trails for the Canadian Ski Marathon, the famous two-day, 100-mile ski in the Laurentian Mountains near Ottawa that draws thousands of skiers every February. Clem Holden quickly discovered that working on trails and running a chain-saw was almost as fun as skiing. Both Sylvia and Clem became avid trail workers in the fall, then donned skis to enjoy their handiwork in the winter.

The Holdens would return to Vermont on weekends to visit family and ski. When the Bolton Valley ski area opened in 1966, Clem Holden returned to his old haunt. He enjoyed riding the new lifts, but his real passion was to ski uphill. The downhill ski trails were “nice if you had a long hike up the mountain and then had an easy ride down on the trails. We weren’t anti-alpine skiing at all. We just didn’t want skiers on our trails.”

Soon after the ski area was built, Clem Holden met Gardiner Lane, a veritable Pied Piper of Nordic skiing who founded Bolton’s humble cross-country ski center in the late 1960s. I remember frequently meeting Lane in his “base lodge:” a small, nondescript building with a dirt floor and wood stove that passed as Bolton’s Nordic center. Lane was an elfish man with a big heart who was always full of cheer and good advice about where the skiing was best.

Clem Holden and Lane became fast friends. “Gardiner was a perfect skier —really stylish,” reminisces Holden. “He never went fast. None of us did.”

Lane led a frenetic era of trail cutting at Bolton. In 1972, Lane and Johannes von Trapp cut the 9.4-mile-long Bolton-Trapp trail that links Bolton Valley with the Trapp Family Lodge. That same year, Lane and Holden began cutting a trail from the top of the Bolton Valley ski area to the Waterbury Dam. But they couldn’t muster a crew to finish the job, so that effort was abandoned. In the years that followed, Lane and Holden recruited a group of like-minded retired men and women to clear back-country ski trails with them around Bolton Valley. Word soon got out about the athletic group of old-timers who lived to clear trails and ski them. Holden recalls that in 1992, Burlington Free Press writer Lawrence Pyne came to write a story about the trailblazing retirees. He asked what the group called itself. “I guess you can call us the Old Goats,” replied the self-effacing Holden. The name stuck. Each year, the Old Goats spring to life as winter approaches. “It’s nice to get out in the fall,” Holden tells me. “The leaves are out. And doing a little work didn’t hurt anyone.” Sylvia Holden, a petite woman with a radiant smile who is wearing a green sweater with a gold Christmas tree pin, tells me, “I used to like making bridges. And he did the chainsaw work,” she says, motioning to her husband. Clem Holden says that Olga Vrana, now in her 90s and still active with the Old Goats, told him that “clearing trails was the best time of her life.”

Lasting monuments

The trails that Lane and Holden crafted have stood the test of time — even the abandoned ones. In 1994, Lane received a letter from Catamount Trail Association skiers Cilia Kimberly and Jerry Lasky —aka, the Young Catamounts (“We just call them young but they’re in their 50s and 60s,” Clem Holden chuckles). It included a picture of an old trail sign that the Young Catamounts discovered in the woods while bushwhacking up from the Waterbury Dam. Lane and Holden had placed that sign 20 years earlier. Gardiner Lane wrote of learning that his signature trail had been rediscovered, “Like the explorers Freeman and Lewis and Clark, the Old Goats and the Young Catamounts were stimulated and reactivated the work on the Woodward Mountain trail.” In March 1997, Lane, then 83, and Clem Holden, then 73, set out with Jerry Lasky, Cilla Kimberly and Bolton Valley Nordic Director Tami Bass for the inaugural ski run down the Woodward Mountain ‘frail. “The trail was steep, the snow was deep, the hearts were beating fast,” wrote Lane of the epic six-mile powder skiing adventure. At one point on the ski tour, Kimberly recalls that the younger skiers offered the Old Goats the opportunity to turn back. “There wasn’t even a hesitation. They said, ‘We’re going for it,– she recounts.

Kimberly says that Holden is a mentor to her and many local backcountry skiers. “He’s like a kid when he’s out in the woods, especially when there’s snow. He just expresses the joy of being out there. When he smiles, everyone gets that excite-ment.” “We all want to be like Clem,” she muses. Today, thousands of skiers come from as close as Burlington and as far as Montreal, Boston and New York to ski the gems of the Bolton Valley backcountry that Holden and the Old Goats blazed. The Bolton Trapp Trail may be the most popular backcountry ski tour in Vermont. The Woodward Mountain Trail is a hallowed powder stash. Numerous other trails that were cut by the Old Goats — including Heavenly Highway, Paradise Pass and Devil’s Drop — are skied daily by locals. “It is easily accessible and it’s some of the best backcountry skiing in the state of Vermont, if not in New England,” says Catamount ‘frail Association Director Jim Fredericks.

Despite its riches, Bolton Valley has teteered on the edge of survival. The downhill ski resort has had multiple owners and been in and out of bankruptcy. During the 1998-1999 winter, the ski area was closed due to financial problems. But Lane convinced the town of Bolton to plow to road to the cross-country ski center, and he and Holden kept the center open. “It was like a party all winter long,” recalls Ann Go-tham, a local nurse, longtime Bolton Nordic ski patroller, and Old Goat. “These old guys would warm the place up and serve soup and they had a lot of fun. They always had fun.” (When I question how Gotham, a spry 56 year old, qualifies as an Old Goat, she explains that while men had to be over 60 to be an Old Goat, “young women were always automatically accepted.”) Holden shows me to his neatly-kept garage in Btu-ling-ton. He walks past a half-dozen backcountry skis to proudly show me a large handwritten sign. “To Gardiner and Clem — Thank you for making ’98-99 a year to cherish. — Love, The Skiers.”

Saving the trails

The last trail that Holden and Lane cut together was a ski trail around a pond at Shelburne Bay Senior Living where Lane lived. Clem and Sylvia Holden stayed close to Lane until his death in 2005 at the age of 90. Clem Holden has persevered through his own health challenges, including heart surgery and breaking both his legs while hiking in the Adirondacks three years ago, and breaking his hip in a fall last week. Sylvia Holden no longer skis, preferring to snowshoe instead. Clem still skis every chance he gets, though his hip injury will keep him off the trails this winter. In February 2011, word got out that most of the Bolton Valley Nordic and backcountry trails were to be sold to a private individual. Public access to the land would be lost. Ann Gotham rallied local backcountry users and formed the Friends of Bolton Valley Nordic and Back-country to try to save the land. In March 2012, The Vermont Land Trust (vlt.org) called a meeting in Richmond to begin raising money for one of its most ambitious conservation efforts ever — to preserve more than 1,100 acres of backcountry land around Bolton for public use. The Old Goats swooped in to save their snowy habitat. Clem Holden showed up at the kickoff meeting and wrote a $5,000 check on the spot — the project’s first donation. The Vermont Land Trust must raise $1.8 million to protect the Bolton lands forever. Remarkably, they are just $175,000 shy of their goal. The land trust has until April 1 to close the gap. “If I’d won the lottery I would have bought it myself,” Clem Holden says. Saving Bolton is the culmination of a lifelong love affair that Clem Holden has had with the mountains that he has explored since boyhood. It is also a poignant tribute to his dear friend, Gardiner Lane. Sitting in their living room with Lane’s beautiful watercolor paintings hanging on the walls, Sylvia Holden reflects on their friend’s passing. “As you get older you have more acceptance of these things,” she says gently. “We feel as though there comes a time.” Clem Holden looks restless. He seems torn between heading out for a ski or just speaking his mind. He chooses the latter. “There comes a time, but there’s no rush,” he interjects. He breaks into a grin, crowned as always by his snowy pate. “We’re having too much fun.”

Final note. BoltonFriends and Vermont Land Trust did raise 1.8 million dollars, bought 11,000 acres and on June 13th 2013 turned the deed over to the State of Vermont, making it part of the Mt. Mansfield State Forest and preserving public access forever — Editor.